What were battles like in the time of King Alfred? Organised shield walls or brutal melees? Did they use cavalry? And what about fights at sea? Chris Bishop examines the ways of war in the 9th century.

As King Alfred spent so much of his reign at war with the Vikings (or with the Danes to be more precise) it seems only fitting to consider how battles were actually conducted at what was surely a significant turning point in English History.

I should perhaps start by distinguishing between the major battles at this time and raids. It would seem that the latter were commonplace and often carried out as ‘hit and run’ attacks by relatively small groups of Danes brutally targeting farmsteads and smaller settlements as well as more lucrative objectives such as the churches and monasteries.

Battles, on the other hand, would have involved much larger groups, some of them big enough to constitute an army. It’s difficult to define ‘an army’ in purely numerical terms but is likely to have comprised at least several hundred men and sometimes considerably more. So far as the Danes were concerned, their larger armies often comprised several contingents, each with its own ‘warlord’ – as was the case in the invasion of The Great Heathen Horde in 865.

At this time battles are often depicted as a melee of brutal hand-to-hand fighting involving a fearsome array of weapons. All the evidence we have seems to confirm this although much of it was recorded by monks to whom any conflict might have appeared as particularly violent.

That said, battles may not have been quite as ‘spontaneous’ as you might think. Given that most of the combatants would have arrived on foot, it seems probable that they may have rested before throwing themselves headlong into the fray and perhaps even tried to discuss a peaceful resolution before commencing hostilities.

There is also a suggestion that both sides took time to agree and mark out the parameters of the battlefield with wands of hazelwood or determined it by reference to notable landmarks such as rivers or ditches etc.

Some battles are said to have lasted all day – pretty exhausting when you think of wielding a heavy weapon whilst fighting at such close quarters. I’ve tried a replica sword and found that my arm tired after just a few dozen strokes. In fact, it has been suggested that some warriors might actually have taken a rest break (presumably in rotation!) during a battle to allow themselves to recuperate from their exertions.

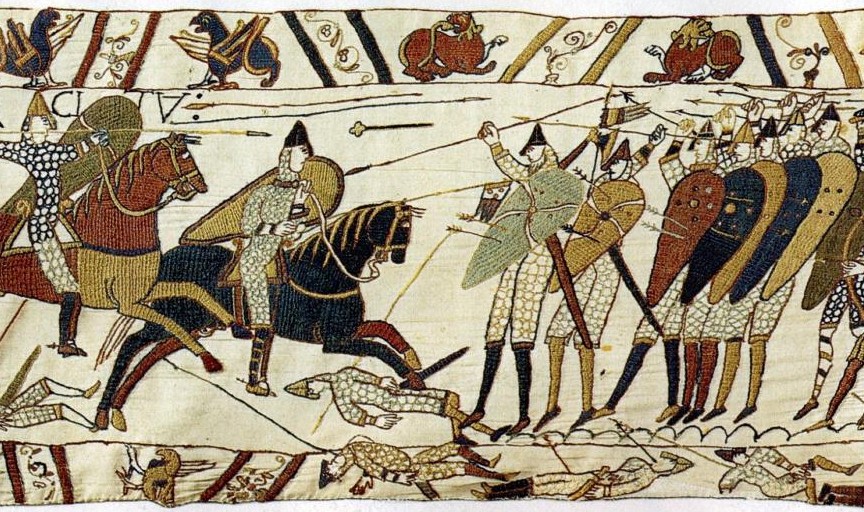

Apart from a frenzied ‘head on’ charge or an ambush, the most notable tactic which might have been employed is that of the shield wall.

I’ve seen varying suggestions as to how the shield wall might have been formed and deployed but, in essence, it seems to have involved forming your men into several rows with those at the front interlocking or overlapping their shields and those behind them trying to skewer the enemy through any gaps. There may have been another row using their shields to protect the others from projectiles.

Whatever the formation, those in the shield wall would have had limited mobility so I do wonder whether it may have been a largely defensive measure, useful when outnumbered but leaving the front rank too constricted to wield their weapons effectively.

Whilst it’s likely that the shield wall would have been a tactic employed by both the Saxons and the Danes, logically one side would have to attack the other, perhaps forming a wedge to slam home their assault on any weak spot before spreading out along the full length of the line, hacking and probing with their weapons as they tried to open up a breach. Once achieved, the battle would no doubt have descended in a melee of hand-to-hand combat.

Obviously, those commanding the ranks would have stood at the back to direct operations, perhaps using runners to relay messages to whoever was in overall command or to request reinforcements and so on.

Sieges

It seems that the usual tactic employed for a siege involved either starving the defenders of a fortified place into surrender or battering down the gates to gain entry. This suggests that siege engines such as towers or catapults were not used, although fire and some form of battering ram are likely to have been involved.

There are several references to armies being surrounded and then starved into submission. An example of this was at a place called Buttindon on the banks of the Severn where it’s reported that the Danes were contained for so long that they were forced to eat their horses!

The use of cavalry

The perceived wisdom is that battles at this time were normally fought on foot but it has been argued by some historians that this might not always have been the case. Indeed, it does seem logical that a man wealthy enough to own a horse might well have ridden it into battle for whatever tactical advantage he could achieve by doing so.

However, more typically, we are led to believe that whilst the wealthier men and nobles may have ridden to the battlefield, once there they sent their horses to the rear and fought on foot like everyone else.

There is a certain amount of logic in this. As not many men could afford to own a suitable horse, being one of only a few men mounted would mark out a warrior as a person of wealth and status, making him an obvious target. A horse would also have been easier to hit with an arrow amid the turmoil of battle – bring it down and the rider must surely follow, probably injuring himself and others in the process.

There is also the risk of having frightened and wounded horses running loose on the battlefield which would have posed a significant danger to those fighting on foot, not to mention the distraction and disruption caused if they interfered with the battle tactics and formations.

In fact, it’s probable that the first time the Saxons faced a cavalry charge was at the battle of Hastings.

Battles at sea

Whilst there are references to battles at sea in this era off both the coast of Britain and mainland Europe, most of the information they provide focuses on the number of ships involved and the outcome, with very little about the tactics employed or how these battles were actually fought.

Some accounts suggest that the ships were sometimes roped together to form a floating ‘platform’ from which the men would fight much as they did on land – with a shield wall for protection supported by arrows and other projectiles. This was apparently followed by boarding and then hand to hand fighting.

Whether this form of battle was used by both the Saxons and the Danes isn’t clear, and it may be that a variety of other tactics were employed, some perhaps amounting to little more than a show of strength or a pursuit to see off the opposition.

Either way, in order not to be constrained by wind strength and direction whilst actually engaged in a battle, it’s likely that the sails would have been furled leaving the ships to rely on their oars for propulsion and manoeuvrability. An obvious objective might therefore have been to kill the oarsmen and thereby render the ship at least temporarily immobile.

It’s doubtful they would have rammed each other for fear of damaging their own vessel but I have read suggestions that they might have tried to ‘shear off’ the oars by sailing close alongside the enemy. I’m not sure how practical that would have been without damaging their own oars and, by sailing so close, they would have been vulnerable to boarding.

Similarly, I doubt whether fire played a significant part in a sea battle as, with the sail furled, it would have been relatively easy to extinguish and any change in wind direction or tide could mean that the burning vessel drifted back into your own fleet. Besides, taking a ship intact would have been a valuable prize and not one you would destroy unless you had to.

Logically, these battles would have been fought in the quieter coastal waters, or river estuaries and were probably not as epic as might be envisaged. The Danes relied on the tactics of shock and surprise so, once they’d been sighted, they might well have preferred to sail away and try their luck elsewhere, particularly as it’s thought that they didn’t much relish fighting at sea. After all, a damaged ship could make it difficult to sail home or, at the very least, necessitate repairs.

My conclusion from the above is that battles were perhaps a bit more organised than is sometimes depicted but every bit as fearsome – certainly not something to be entered into lightly!

Hence the payment of tribute for the Danes to go away was not uncommon, although the prospect of getting a ‘second bite of the cherry’ was incentive enough for them to return again afterwards. Whatever tactics were employed, the outcome of a battle was not always decisive and sometimes ended with a sort of ‘no score draw.’

Whilst not universally accepted, the above thoughts and observations are my own and are based on the research I undertook for my books inthe Shadow of the Raven series.

If you’ve enjoyed Chris’s feature, you may like to dig a little deeper in another two he’s written: Horses in battle at the time of Alfred the Great and Was King Alfred really the father of the English navy?

Images:

- Illustration from The Cædmon Manuscript, c1000, MS Junius 11: © Bodeian Digital via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Illustration from Life of Guthlac (the ‘Guthlac Roll’), Harley Y 6, 12th century: © British Library Board (CC BY 4.0)

- Bayeux Tapestry section showing Norman horses charging English foot-soldiers in a shieldwall: Silvia Calderon via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

- Pre-1066 illustration of Anglo-Saxon warriors on horseback, Harleian MSS CO3, from Larson, LM (1912), Canute the Great 995 (circ.)–1035 and the Rise of Danish Imperialism During the Viking Age: via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Oseberg Ship, before 835: Макс Вальтер for Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- The Sea Stallion, a replica based on the remains of the Viking longship Skuldelev 2, found sunk in Roskilde harbour in Denmark: © Emma Groeneveld for World History Encyclopedia (Creative Commons Attribution)

FIRST PUBLISHED IN HISTORIA, THE ONLINE MAGAZINE FOR THE HISTORICAL WRITERS’ ASSOCIATION